Your mother always told you that if something was bothering you, you should talk about it. It would make you feel better. Turns out she was right, and researchers at the School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering have the science to prove it. Johan Bollen, a professor of informatics and computing, leads a team that analyzed the Twitter feeds of tens of thousands of users to study how emotions change before and after they were explicitly stated. In the study, “The minute-scale dynamics of online emotions reveal the effects of affect labeling,” published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, Bollen and his colleagues used algorithms to measure how the positivity or negativity of tweets change before or after a user explicitly expressed having an emotion, e.g. saying “I feel bad” or “I feel good.” Their study not only reveals how emotions evolve over time, but also how their expression may change them, and how these changes differ between men and women.

“We looked for people explicitly declaring that they were having an emotion,” Bollen said. “We have so much Twitter data that the odds of someone saying exactly what we are looking for are actually pretty good. In fact, we found tens of thousands of such cases. Once we knew that someone, male or female, was having a feeling, we could measure changes in the sentiment of their tweets before and after the statement. This resulted in a minute-by-minute timeline that shows how the underlying emotion changed over time.”

The results were pretty clear.

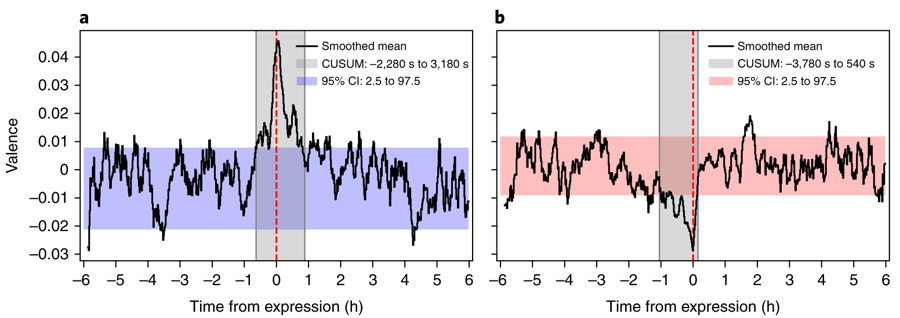

“If a person was feeling good, the preceding tweets gradually became more positive before the statement, even if they weren’t about the feeling,” Bollen said. “Then, immediately afterwards, emotional levels quickly returned to the baseline. Interestingly, for negative emotions, this same pattern was even more pronounced. That tells us a number of things. First, even when people are not explicitly trying to express an emotion, their language can still give it away. Second, when emotions are expressed, they immediately start to fall back to neutral levels. Third, expressing negative emotions may be most beneficial, because they respond the fastest.”

The phenomenon, known as “affect labeling,” had previously been studied in laboratory settings, but the results of the Bollen study allowed researchers to study individuals’ emotions without directly interacting with them, revealing the minute-by-minute ebbs and flows of naturally occurring emotions.

“You may think that emotions can change independently from the language that we use,” Bollen said. “But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Language and emotions do interact, both ways. The roots of an emotion are revealed in your language prior to your expressing it, but when you express the emotion, it may also changes the emotion. Just saying the words ‘I feel bad’ almost immediately brought emotions back down to the baseline. I think it is also interesting that women and men differ in the degree to which they benefit from this effect.”

The study points to a simple and straightforward strategy that could be employed to help people feel better: putting a label on an emotion and saying it out loud. This could have ramifications for researchers studying mental health issues which are often associated with emotional changes. Bollen et al are studying how mental health disorders can be traced and potentially predicted from social media data. This work may yield new insights into these disorders which may potentially contribute to effort for their prevention and treatment.